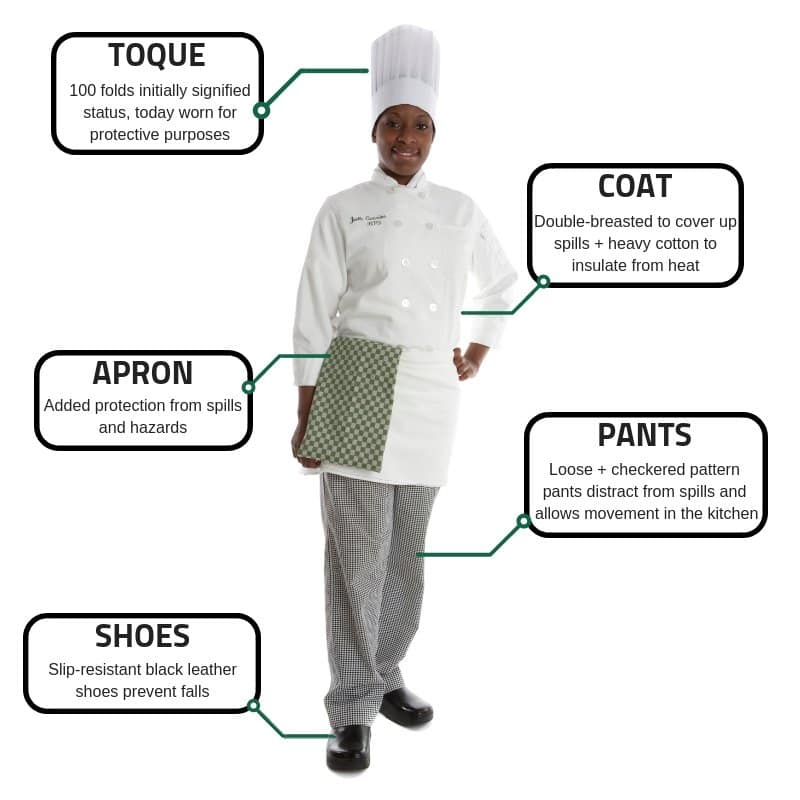

It’s all about pride. If you have it in your profession, you will have it in your uniform, no matter what your walk of life. With the chef’s uniform, there is more at stake than just keeping the uniform clean and white. A dignified look helps generate a feeling of professionalism. When you don the toque, jacket, checkered pants, neckerchief, apron, and side towel, you are continuing a centuries-old tradition. It is a standard of dress which evokes an instant sense of recognition, telling both foodservice industry insiders and the public that they are in the presence of a skilled practitioner. Each element plays an important role in keeping workers safe and comfortable in a potentially dangerous environment.

At the Culinary Institute of America, our students receive pants and chef’s jackets with their names embroidered on the chest upon entering our degree programs in Culinary Arts or Baking and Pastry Arts. For kitchen classes, the undergraduates also must wear cleaned and polished black leather shoes, white neckerchief, apron, side towel, and toque. Upon graduation, they each receive another jacket with the word “alumnus” or “alumna” embroidered above the college’s logo on the breast pocket.

The chef’s uniform has evolved over many generations. Four factors contributed to the evolution of the uniform: A practical need for protection; an aesthetic need to present a clean, professional image; to confer distinction, establish status, and denote pride; and finally, the uniform removes the need for being different by wearing uniquely-styled components. The uniform is a common denominator, creating a team spirit while encouraging a focus on what we are doing rather than our appearances. The contemporary uniform reflects both its practical and utilitarian aspects as well as its mythical and romantic tradition.

In medieval times, the distinguishing mark of a chef was an apron. In fifteenth-century illustrations of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the cook is shown wearing an apron. In Debate between Pride and Lowliness by F. Thynn, written in 1568, a man is described as wearing “a white knitt cappe. I judged him a baker by trade.” By the Victorian Era, prints and illustrations portrayed chefs in white clothing, with a white cap resembling a night cap or tam-o-shanter. Thackeray’s 1852 story, A Little Dinner at Timmins’s, describes a chef wearing a crimson velvet waistcoat and “a white hat worn on one side of his long curling ringlets.”

There are many legends as to how the various parts of the uniform—from the toque to the shoes—became the standard.

The Toque

The chef’s hat, or toque, goes back to ancient times. Thousands of years ago in Assyria, poisoning was a common way for a person to rid himself of enemies. Aware of this problem, Assyrian royalty selected their cooks carefully. They chose only their most loyal subjects to be their chefs, sometimes even members of the royal family itself, and made them members of the court. Responsible for the kings’ safety, chefs were paid handsomely in money and land, to avoid the temptation of being bribed by the kings’ enemies. They were entitled to wear a crown of a similar shape to the royal family employing them, although made of cloth and lacking in jewels. Some believe the crown-shaped ribs of the royal headdress developed into the pleats of a chef’s hat. Legend has it that the approximately 100 pleats on today’s toques represent the number of ways a chef knows how to prepare an egg. That story is attributed at various times to ancient Persia, Rome, or France.

During the zenith of the Greek and Roman Empires, chefs presided over gluttonous feasts and were called before the royal court to be ceremoniously “crowned” with a bonnet-style cap studded with laurel leaves.

Another story is that the modern toque is patterned after the headdress of Greek Orthodox priests. By the end of the sixth century AD, the Byzantine empire was being overtaken by Barbarians. Philosophers and artists were targeted by the invaders. (Cooks were considered on the same level as philosophers. In fact, the word “epicurean” used to mean food lover, comes from the Greek philosopher Epicures.) These philosophers, cooks, and other artists fled, taking refuge in Greek monasteries. While in hiding, they dressed as priests. But out of respect to the clergymen, the chefs changed the color of their hats from black to white.

By the 16th century, the height, shape, and stiffness of the hat varied by country. The French had a flattened beret, Italians wore theirs medium height with formal pleats, and the Germans had a softly gathered style.

Two centuries later, French chefs were seen wearing a “casque à méche” or stocking cap, with different colors determining the rank. At the same time, Spanish cooks donned white wool berets while Germans wore pointed Napoleonic hats with a decorative tassel.

In England, the cooks wore black hats. British cuisine—known as Baronial cooking in the middle ages—usually consisted of a huge roast of beef, lamb, wild boar, or venison cooked on a spit in a huge wood-burning hearth. The chefs had to spend long hours stoking the fires and reaching into the hearth to tend to the meats. As a result, they would get soot and ash on their hats. Black, therefore, was a functional color for these chefs. Their caps were often pressed flat, enabling them to carry food on their heads, as the kitchen was usually quite far from the dining area.

Well into the 20th century, English cooks continued to wear small black hats resembling a librarian’s skull cap. This type of headgear was neither cool nor comfortable, and not very practical for regular stove work, and therefore became a symbol of the “master cook” or kitchen supervisor.

During the reign of Napoleon III (1808–1833), bald cooks purportedly were made to wear velour or heavy cloth caps, while those with hair wore linen or netting.

Also in the early 19th century, Chef Boucher, who cooked for the Prince of Talleyrand, insisted that everyone in his kitchen wear a white toque for sanitary reasons. It kept hair up and out of the food, while absorbing some of the moisture from an overheated brow. And the tower of air inside the chef’s hat kept the head cool in a hot kitchen.

Auguste Escoffier (1846–1935), the father of modern cuisine, favored the comfort and imposing appearance of the tall, starched, and pleated hat, which became known as the white toque or “La Toque Blanche.” Originally the ribs or pleats were stitched into the cloth. Later they were stiffened with starch. The term “toque” stuck, even though it is actually the French word for a soft, brimless, and usually small hat.

“A cuisinier is judged worthy to wear La Toque Blanche only through his perfect workmanship,” Escoffier once said. He developed the practice of different toque heights to delineate rank in the kitchen. That way anyone entering the kitchen would know who was in charge, as well as the status of each person working there.

Marie-Antoine Carême, while chef to Lord Stewart, the English Ambassador to Vienna, is credited with introducing the starched high hat. He tucked a piece of round cardboard inside a flattened, starched toque. This style, illustrated in his 1822 book Le Maître d’Hôtel, quickly caught on in Vienna and Paris, but apparently remained unfashionable to British cooks until this century. His tome is credited with promoting the elements which comprise the modern day chef’s uniform.

Alfred Suzanne has a definitive date for the toque becoming a standard part of the chef’s uniform. The author of La Cuisine Anglaise wrote in 1894 that the toque replaced the bonnet or beret-style hat in kitchens 54 years earlier (in 1840). He was not a proponent of the shape, however, calling it “as ridiculous as uncomfortable.” Suzanne added, “The toque called ‘Eiffel Tower,’ elongated perpendicularly, is the favorite headdress of small people who look to increase their size in the eyes of their subordinates. This hat has a vulgar aspect.”

Today’s top chefs wear toques approximately 12 inches tall, while apprentices and amateurs have eight-inch hats. As recently as the 1960s, toque manufacturers kept files on each of the chefs for whom they made hats, including height, weight, hat size, and rank in the kitchen. From this information, they could make the perfect toque to order at the chef’s request.

Harold McGee, in The Curious Cook, a book on kitchen science and lore, favors a simple baseball-style cap over the toque for at least one purpose: oil droplets rising from a pan will fall and settle on the inside of a chef’s glasses, unless the chef is wearing a visored cap.

The Jacket

The double-breasted jacket was portrayed in Marie-Antoine Carême’s 1822 illustration, and was in full vogue by 1878, when Cerubino Angelica of Angelica Uniform Group began manufacturing them. The advantage of these unique wide-flapped jackets was that if the front of the jacket became soiled, the flaps could be reversed—with the dirty one hidden behind—to create a better appearance. Thus, the chef could wear a clean jacket for twice as long. In addition, there were two layers of protection from spills, splashes, heat, and steam.

Since the jacket buttons either way, it is equally appropriate for men and women. Today, its unisex style reflects the fact that the term “chef” does not denote gender.

The jackets were also fitted with longer sleeves than necessary. This was to protect the arms from burns in case of inadvertent contact with hot oven doors, and to allow the chef to grab the cuffs in his hand to use as instant oven mitts if he had to touch a hot pan or reach over an open flame.

The Side Towel

Nowadays, most chefs use side towels to protect their hands while lifting hot items from the stove or oven. When not using the towel, it is tucked into the string of the apron. The side towel is not meant to be used as a wiping cloth. If, out of habit or instinct, a spill is cleared with a side towel it should be replaced immediately. Once they become even slightly wet, side towels can no longer insulate the hands. Instead, they will conduct the heat, which will move quickly through the moisture. (And if you drop the pot when you burn your hands, you are liable to give yourself or others burns on the legs and feet from the splash.)

The Apron

Aprons are worn over the jacket and midsection to protect the uniform as well as the chef. With chefs cooking and reaching over large open flames, the apron was historically a safety measure. Now it is worn to keep the uniform clean, protecting the jacket and pants from spills, scalds, and stains. From an 1892 London cookery class for apprentices: “Reversing the apron once is permissible and by adjusting the number of folds (over the waist string) stains can be hidden.” The instructor, however, warned the chefs-to-be against making the apron “ludicrously short” by folding it too much.

The Trousers

A chef’s trousers have a small checkered pattern, which is effective in disguising the inevitable stains which develop while working. In the United States, the pattern is usually a black and white houndstooth, while many chefs in Europe prefer a blue and white pattern.

The Shoes

High-quality, supportive, and protective footwear is an often overlooked part of the uniform, but also a very important part, a fact to which anyone who stands on a line all day can attest. Hard leather shoes with slip-resistant soles are recommended, both for protection and support.

Since everybody’s feet and comfort levels are unique, the Culinary Institute of America’s book, The New Professional Chef, recommends taking the time and effort to try on several different types of shoes to determine which are most suitable. Neglecting your feet is bad business, and can result in foot pain, back trouble, and possible permanent discomfort. If you develop trouble with your feet, seek professional help, consider orthotics, and carefully heed advice about what shoes and other devices may be best for your particular needs.

At CIA, we also teach our students that sneakers or athletic shoes are never appropriate in the kitchen. While they are comfortable, they do not provide the necessary protection from dropped sharp objects or hot liquids.

The Neckerchief

The neckerchief tied cravate-style currently adds the same finishing touch to a uniform as a necktie does to a business suit. Originally, when kitchens were unbearably hot, the neckerchief caught and absorbed facial perspiration. It also had a medical purpose, keeping the neck and throat areas protected from the extreme temperature fluctuations between the stove tops and the coolers. If the neck got too hot then too cold, the chef could take ill, catching cold, or worse yet, pneumonia.

Although many modern chefs try to spice up their uniforms as they do their food, with numerous color combinations, the white uniform is classic. In any kitchen seen from the dining room, an all-white uniform gives an impression of cleanliness and purity, which you want to impart to your customers. Although some chefs prefer not to wear a toque, Roger Fessaguet, the former owner of La Caravelle and president of Vatel Club, puts it best. “Could you think of a policeman without a hat? That is part of the full uniform,” he said. “It’s a sign of respect for the chef.”

Cotton fabrics are still favored over synthetics, because cotton is more comfortable in the heat of a kitchen. The material also must be strong enough to withstand frequent laundering.

The laundering of the uniform is the final important element. The pants and jacket should be washed at the end of each shift. Aprons and neckerchiefs must be changed during the course of the shift if they become soiled. The jacket should be kept as white and sanitary as possible, as clothing can harbor bacteria, molds, parasites, and even viruses which can be transferred to the food.

When you walk into the kitchen with a bright clean uniform at the beginning of a new day, it is not only a measure of the pride you have in your appearance, your skills, and your profession, it is also a matter of health for your customers. You are showing that you are a member of a team, and a practitioner of a noble and ancient craft.

Do you see yourself in a chef’s uniform?

Learn more about how CIA can help you transform your life’s passion into a purposeful career.