Hi, it’s Majestic again, back for more culinary science fun! Recently in one of my Flavor Science labs, we experimented with egg making. We made omelets! Everyone loves a hot fresh omelet, right? Creating an omelet is actually more complex than it seems. There are so many molecular properties involved that many people don’t consider or even think about. Let me tell you why our professor, Chef Jonathan Zearfoss, decided to let us cook up some eggs—and the surprising results that followed!

There are dozens upon dozens of ways to make an omelet. Chefs have their own preferred methods to make it just the way they like it. Here are three popular techniques:

- The French Omelet—According to master culinary scientist Harold McGee, the fastest way to make an omelet is to have a hotter pan for fast cooking. This technique requires the eggs to be scrambled vigorously with a fork or spoon in a hot pan until they begin to set. The curds are then pushed into a disk while the bottoms consolidate. The pan is then shaken to release the disk and folded onto itself.

- The American Omelet—Another variation is to turn down the heat and let the bottom of the omelet mix set first, then use a fork to lift one of the edges while tipping the pan. This allows the liquid to run underneath the forming omelet, which produces a thicker, denser omelet. This process is repeated until the top is no longer runny and the mass is then folded over.

- Omelet Soufflé—A third variation is to whip the eggs until they are full of bubbles or whipping the egg whites separately into a foam and then adding them back to the yolks. The omelet soufflé yields a noticeably lighter texture compared to other methods. If the eggs are left undisturbed for a while, the bottom surface sets. This yields a more uniform looking skin.

These examples show the various ways an omelet can be made. Each could yield different results that subsequently affect the texture, appearance, and even the flavor of the formed omelet. Why, you ask? It’s simple: egg proteins change depending on how they are prepared.

The Science of the Egg

An egg is made up of nine main components and properties. These properties are the shell, yolk, air cell, shell membrane, chalaza, thick and thin albumen, vitelline membrane, and germinal disc. Egg proteins contain hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids. This essentially means that eggs, especially whites, have globular proteins.

The variation used in this lab experiment was a whisking technique; air incorporation vs. no air incorporation. Beating and whisking eggs creates structure. When eggs are beaten or whipped, the proteins denature and unfold. When air is incorporated into liquids, the solution traps air bubbles. This foaming ability effects the texture, cell structure, and appearance of the final product.

Time to Cook—and Experiment!

Now that I’ve explained the science behind eggs, let’s talk about the cooking! Two omelets were made in total. One omelet was the control, or the unchanged omelet, which we labeled A, and the other omelet was the variation, which we labeled B. Both omelets received the same amount of ingredients:

Ingredients Amount

Heavy Cream 10 Grams

Kosher Salt 1 Gram

Egg Whites 80 Grams

Egg Yolks 40 Grams

Grape Seed Oil 5 Grams

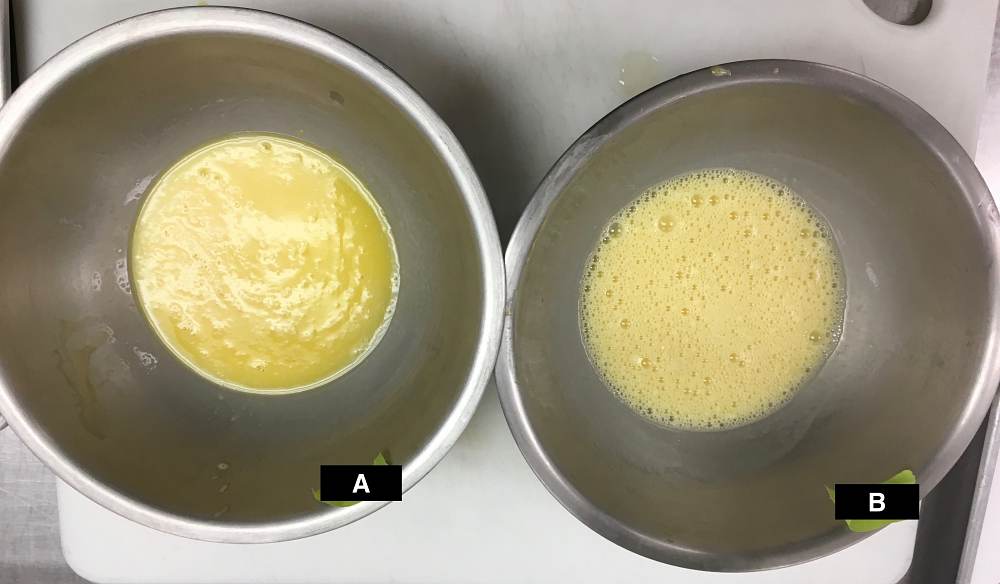

My lab partner and I were very excited to whisk up these eggs! My partner whisked and cooked omelet A for 1.5 minutes, while I whisked and cooked omelet B for 3 minutes. Then we measured the temperatures for each. Omelet liquid A was measured to be 13.4°C while omelet liquid B was measured to be 14.8°C after whisking. After whisking, omelet A was blended well and displayed very few bubbles. Omelet B, however, had very noticeable bubbles ranging in size and displayed a lighter color.

Both omelets were cooked on two separate induction burners. At the same time and sequence, the measured salt was dissolved in the measured heavy cream. The salted cream was then combined with the egg whites and yolks and whisked until the mixture was blended. The sauté pans were then preheated on medium heat (power 3) and the grape seed oil was poured into each pan. The omelet mixtures were then added to the pans and stirred regularly until they began to set and form a gel. Once the omelets were completed, one end of the set egg gel was rolled over onto the other and placed on the cutting board. The omelet samples were cut and separated into two groups.

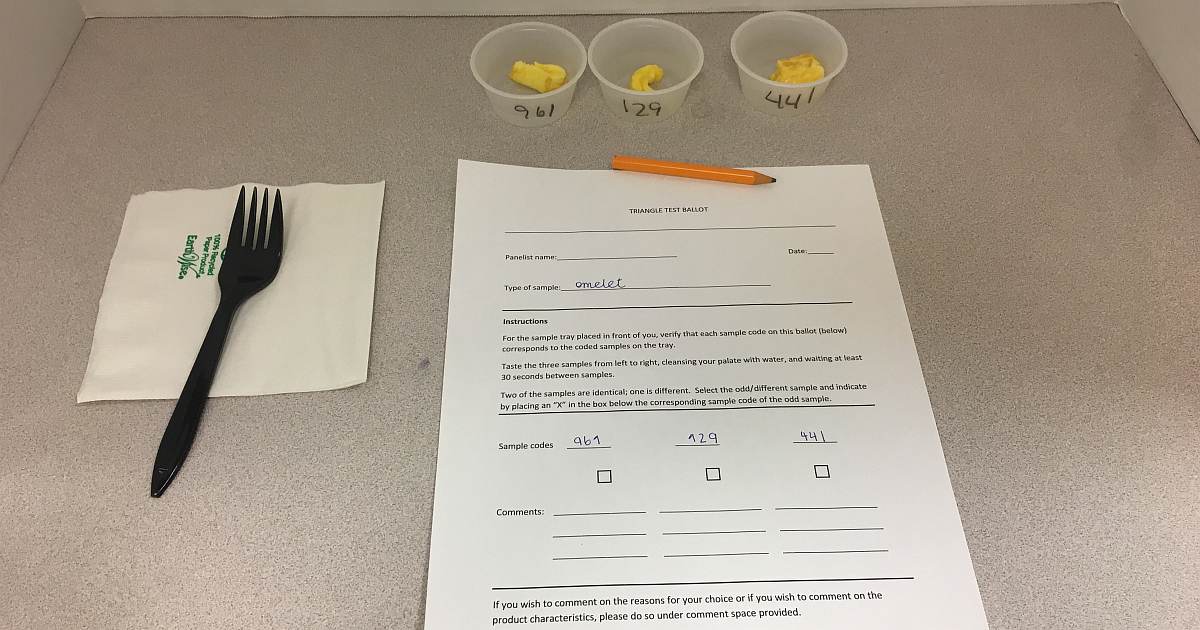

For this experiment, our classmates served as sensory panelists to conduct a Triangle Test, which is used to analyze data—in this case to see if the participants could tell the difference between the two samples. The panelists are presented with three samples—two of the samples are the same and one is different. In this case, the omelets were placed in cups with a random number on it, so the panelists wouldn’t know which omelet was A or B.

The results of the Triangle Test showed that the panelists could not distinguish a difference between the two omelets. What does this mean? Based on the number of panelists, 8 out of the 12 panelists, or 67%, needed to correctly identify the sample (omelet B) that was different to reach the conclusion that they could tell the difference. They did not. Only 50%, or 6 panelists overall, recognized and chose the correct sample.

This experiment showed that although a technique may be changed, panelists may not be able to determine the differences during a sensory Triangle Test. So as you can see, making eggs is no simple task—it’s pure science at its finest! Give this experiment a try, and test to see if your friends and family can detect the difference.

Up next: a biscuit-baking showdown between butter and Crisco!

By Majestic Lewis-Bryant

[starbox id=38]