I started the week wandering the halls of CIA looking for unoccupied chefs and asking them why they skim stocks. It’s been a while since I have interacted with the associate degree program chefs, and most of them just tried to teach me how to make stock, not answer my question—but they gave me answers nonetheless. The consensus of why CIA chefs skim stocks is…there is no consensus! Some skim for color, others for flavor, others to let the stock breathe, and some skim to remove albumen. Needless to say, everyone seems to skim for various reasons, which only reinforces my thesis question: why do we have to skim stocks? I suppose we will know in a few weeks, hopefully.

We had our literature review due this week, a paper discussing the published scientific literature related to the topic. The goal is to gather a better understanding of what is known to the world about the topic, in addition to finding out what is not known. Literature reviews have always been somewhat challenging to me. With my chicken stock topic, the research I had found after two weeks was hardly amounting to a paper. I finally found where my research should go in the last week, and the paper got finished.

This week we also ran the first beta tests to our experiments, starting some unofficial trials to work out the kinks in the experimental design.

I plan on doing two stocks a week for as many weeks as I can. We have around 12 weeks to do the entire experiment, so maybe I can do 24 stocks. This will give me enough replications to provide some statistical data. This is what it’s all about—the experiment must be repeated until there is enough data to show a trend, and then continued with repetitions as much as possible.

I was reminded abruptly in the first week that making stock is a pretty inactive experience, especially if you are not skimming. I put the stock on in identical pots with identical ratios of mirepoix, bones, and water. I put a thermocouple in each pot in the same place, and I let the stocks cook. I recorded the temperatures every 10 minutes for the first hour, and then every 20 minutes until I took the stock off the stove.

It is a good thing we were beta testing because I encountered a few hiccups that I need to account for in my experimental design.

- First: Stock is boring to make. I have to find some use of my time during the stock-making process.

- Second: I only have five hours of lab time a week and stock takes at least four hours to make, not including prepping and bringing it to a simmer.

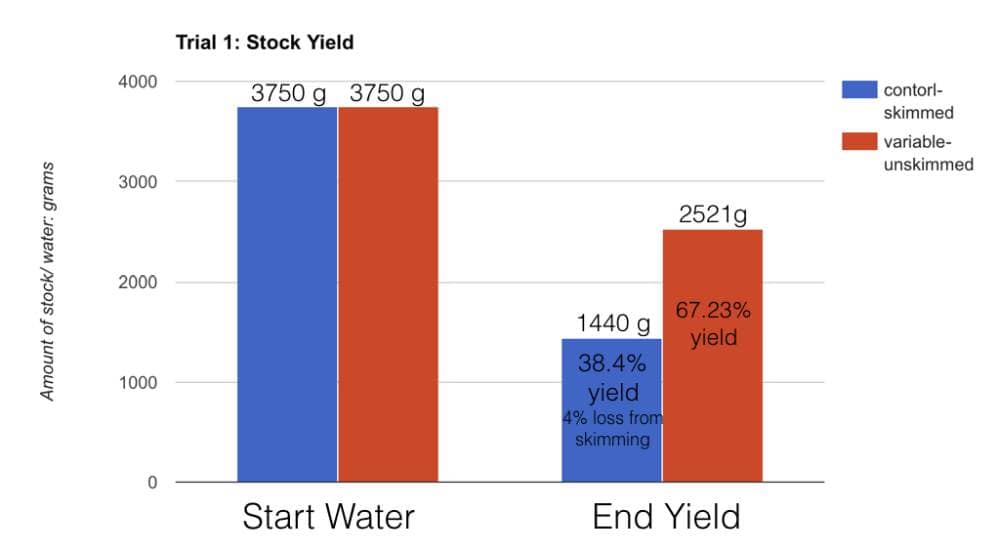

- Third: When I skimmed the stock, it evaporated much faster even though It was the same temperature as the non-skimmed stock. As a result, comparing them is somewhat inaccurate because one is much more concentrated and therefore more flavorful. (My hunch is the fat on the top of the stock forms a sort of lid restricting surface evaporation.)

All of this is good information, and it could’ve been much worse than it was. These are my solutions:

- I will not have time to do measurements on the stock the same day I cook the stock, so I will be freezing the stock each week and doing the measurements on the stock the following week when I make the next stock. This solves the first and second flaws in design.

- I will be cooking each stock for 3.75 hours at 99 degrees C. Once they have been cooked for that time, I will strain the stock, take measurements, and then reduce the stock to 1000g or 1 liter. I will then take measurements of the reduced stocks. Reducing the stocks solve the third hiccup in the design. They will make the concentration of the stock equal for flavor comparison. This is something that is done in the kitchen often. If a stock needs more flavor it would be fortified with more meat or bones or it would be reduced.

This week I had quite a few chefs re-teach me how to make stock, learned how my experiment will be conducted, and found some things I need to improve in the process. I will be making the adjustments above and see where we land next time.

By Alex Telinde